The recent highs in egg prices are almost irresistible material for a pricer to write about, because they give such a clear example of the interaction of supply and demand. Due to avian flu, the supply of eggs hit a low of about 7% below normal levels in February, down from 5% below in January.

However, since people’s demand for eggs was not much reduced even in a constrained market, price tripled with wholesale prices topping $8/dozen in early March, although retailers often took a loss to keep consumer prices lower.

Why such a large price increase for such a small shortfall in supply?

If there are fewer eggs produced, that means that some people need to agree to go home without eggs, or with fewer eggs. But if the price of eggs doubles and everyone still buys the eggs, that means that either we face empty shelves or the price keeps going up until consumption finally goes down. (Looking at shelves over the last couple months, I think we’ve had a combination of both.)

In theory, the way pricing for scarcity it supposed to work is that eggs get allocated to the people who want or need them the most by increasing the price until enough people drop out of the market to make demand match supply. The advantage of this versus just letting eggs sell out is that if you take the keep-prices-the-same-but-sell-out approach, you aren’t so much allocating eggs on the basis of who needs them most, but more on who happens to show up right after another delivery of eggs gets put on the shelf.

Plus, if the retailers aren’t willing to adjust prices based on demand, you’ll end up with an after-market where people who scooped up extra eggs when they had the chance offer to sell them at high prices to people who faced empty shelves and are desperate for some eggs.

However, there’s also a longer-term story to the price of eggs which I discovered as I was researching egg prices, and it’s a fascinating window into some of the major forces shaping our modern economy.

Although prices have been high during the last six months due to avian flu, the overall price of eggs over the last forty years — averaging below $2/dozen in current dollars once adjusted for inflation — is actually significantly lower than during most of the 20th century.

During the 1910s and 1920s, egg prices were over $10/dozen in modern dollars. The reason for this is not unlike the reason that the price of a Thanksgiving turkey has actually dropped on an inflation-adjusted basis over the last century. There have been significant advances in agricultural technology, with modern breeds of birds (and modern types of feed given to birds) growing faster than in the past. But much more important in decreasing costs (and prices) has been the industrialization of farming.

Back in the early 1900s, egg farming was still a comparatively small-scale business. Family farms kept flocks of several hundred chickens and sold the eggs to distributors who shipped the eggs to buyers in towns and cities. Even more locally, many people raised small flocks of hens, and “egg money” was a small but independent source of household money.

All of this was comparatively labor and transportation intensive, and the result was the eggs were not cheap.

Picture a product as being made up of a bundle of costs. For an egg, those costs might be:

A laying hen

Feed and water

Human time to care for hens, collect eggs, transport, clean, package, and sell them

Fuel, electricity and materials for transporting, cleaning, packaging, and refrigerating the eggs

Feed, water, fuel, electricity, and packaging materials are all things which have become less expensive over time. What has become more expensive is human time. What automation and industrialization in farming has done is vastly reduce the amount of human time that goes into each egg before it reaches a customer.

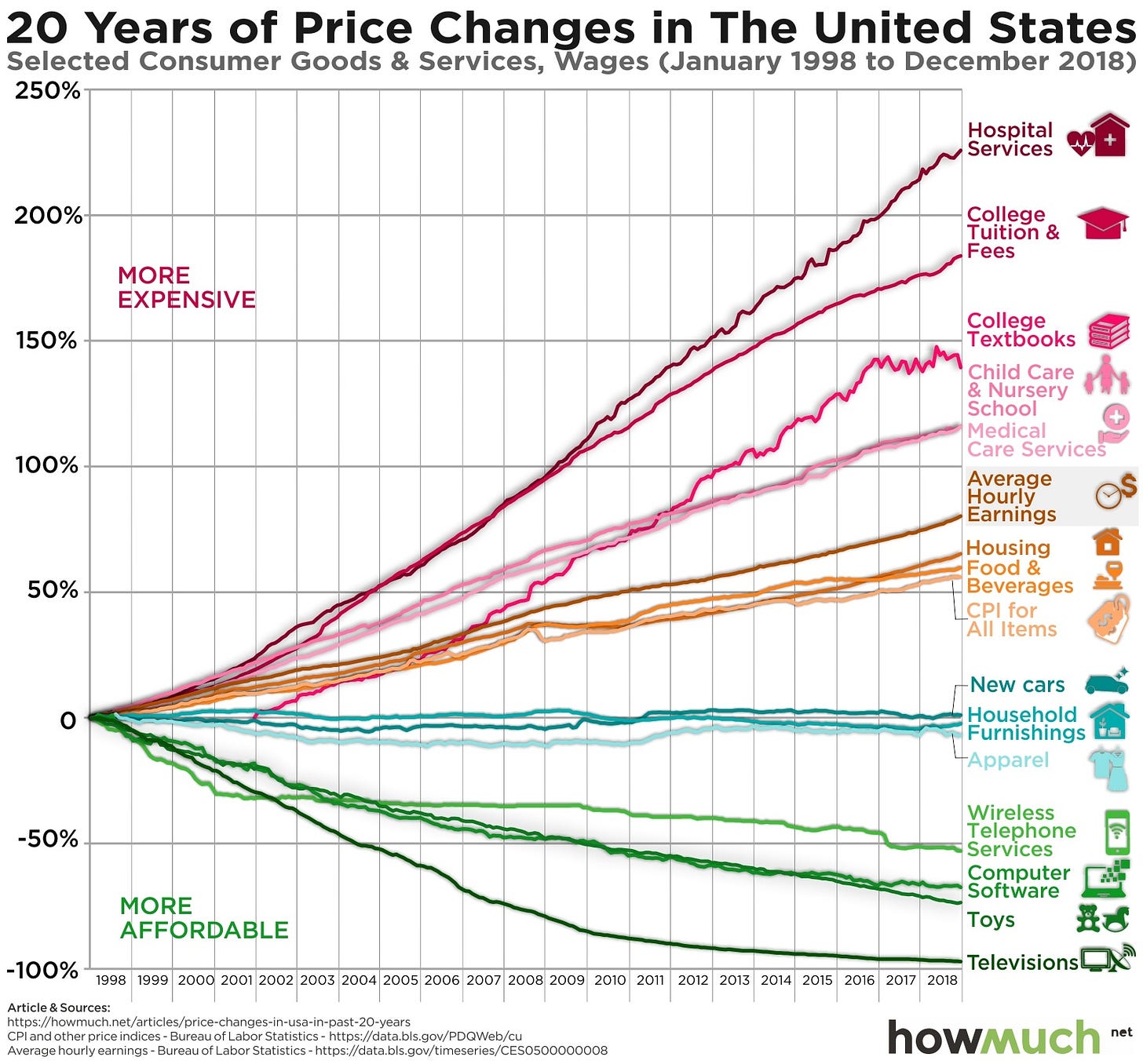

If you’ve ever looked at one of the charts that show price changes over time (such as this one from HowMuch.net, a financial literacy website) you’ll notice that the categories which have become more expensive over time are generally those which involve a lot of direct human time which is hard to eliminate through automation, while the categories which have seen the most decrease in price are those where automation can easily reduce the amount of human time invested in production.

Categories such as health care and education often involve direct interaction with trained professionals in a way that can’t be scaled through technology.

Getting advice from an online medical resource, for instance, is scalable and thus cheap. Similarly, studying online using Kahn Academy or DuoLingo is inexpensive because the resources can be built once and then delivered to many students with very low additional cost.

But going to a medical office and sitting down with doctor or nurse directly is expensive because it always takes up that trained professional’s time. A doctor cannot use technology to diagnose 100 patients simultaneously. And although remote learning does to some extent allow a teacher to teach many classrooms of students simultaneously, successful teaching usually relies on actual interaction within the room between a teacher and a small number of students, not simply listening to a recorded lecture.

At the other end of the spectrum, while there are large early investments of human time in developing the technology and manufacturing methods for consumer electronics such as televisions, once the work has been done they can roll off the production line with very little human time per unit, and once the technology is sufficiently mature there’s increasingly less R&D time being put into new models as well.

Even things which you might think of as being based on human time can be subject to these efficiency savings. For instance, you if hire a bookkeeper to keep the accounts for your small business, you might be paying that bookkeeper by the hour. However, the number of hours it takes your bookkeeper to manage your books now should be less than it would have been 20 much less 40 years ago. Now it’s possible to download all your transactions from your bank in a spreadsheet or connect QuickBooks directly to your bank account.

You’re still paying your bookkeeper by the hour, but the number of hours it takes to record a given number of transactions and prepare a set of reports for you is much less now than it would have been several decades ago.

This higher efficiency in turn allows people to engage in higher value work. Modern data repositories and reporting tools allow today’s finance professionals to quickly provide insights to business leaders that would have taken far more hours to produce in the past.

By comparison, a business like a hair cutter or a makeup artist has not seen productivity gains in its core product in the last few decades, and so the prices of those products will naturally go up at the same rate as the incomes of the practitioners.

This means that if you do the sort of work which is subject to technology-driven productivity gains, you need to constantly be looking for ways to adapt and become more efficient. Your successful competitors will be adopting those technologies, and you will need to do so as well in order to keep up. If you can stay ahead of most of your competitors, this means that you can experience the margin benefit of productivity gains before market prices as a whole have adjusted to the new higher efficiency. So the most successful companies will often be the ones which are quickest to adopt new technology which drives efficiency.

If, on the other hand, you do work in which the human component is pretty constant (as with the haircutter or makeup artist examples) it’s important to take the price changes necessary over time to keep paying your key workers the level of wages that will retain them.

Because so many products decrease in inflation adjusted price over the long term, people are not used to the kind of prices which a human-intensive product or service requires. You will need to make your customers aware that they are paying for the valuable time of skilled workers, so that they see why these more labor-tied prices are worth paying.

Good pricing requires good communication, and if you are to convince customers that your prices need to go up each year even as prices for more technological products go down, you need to clearly convey the artisanal nature of your product.